Book I

Chapter VIII

INTUITIONISM

§2. Further; the common antithesis between ‘intuitive’ and ‘inductive’ morality is misleading in another way: since a moralist may hold the rightness of actions to be cognisable apart from the pleasure produced by them, while yet his method may be properly called Inductive. For he may hold that, just as the generalisations of physical science rest on particular observations, so in ethics general truths can only be reached by induction from judgments or perceptions relating to the rightness or wrongness of particular acts.

For example, when Socrates is said by Aristotle to have applied inductive reasoning to ethical questions, it is this kind of induction which is meant[1]. He discovered, as we are told, the latent ignorance of himself and other men: that is, that they used general terms confidently, without being able, when called upon, to explain the meaning of those terms. His plan for remedying this ignorance was to work towards the true definition of each term, by examining and comparing different instances of its application. Thus the definition of Justice would be sought by comparing different actions commonly judged to be just, and framing a general proposition that would harmonise with all these particular judgments.

So again, in the popular view of Conscience it seems to be often implied that particular judgments are the most trustworthy. `Conscience’ is the accepted popular term for the faculty of moral judgment, as applied to the acts and motives of the person judging; and we most commonly think of the dictates of conscience as relating to particular actions. Thus when a man is bidden, in any particular case, to `trust to his conscience’, it commonly seen is to be meant that he should exercise a faculty of judging morally this particular case without reference to general rules, and even in opposition to conclusions obtained by systematic deduction from such rules. And it is on this view of Conscience that the contempt often expressed for ‘Casuistry’ may be most easily justified: for if the particular case can be satisfactorily settled by conscience without reference to general rules, `Casuistry’, which consists in the application of general rules to particular cases, is at best superfluous. But then, on this view, we shall have no practical need of any such general rules, or of scientific Ethics at all. We may of course form general propositions by induction from these particular conscientious judgments, and arrange them systematically: but any interest which such a system may have will be purely speculative. And this accounts, perhaps, for the indifference or hostility to systematic morality shown by some conscientious persons. For they feel that they can at any rate do without it: and they fear that the cultivation of it may place the mind in a wrong attitude in relation to practice, and prove rather unfavourable than otherwise to the proper development of the practically important faculty manifested or exercised in particular moral judgments.

The view above described may be called, in a sense, `ultra-intuitional’, since, in its most extreme form, it recognises simple immediate intuitions alone and discards as superfluous all modes of reasoning to moral conclusions: and we may find in it one phase or variety of the Intuitional method,—if we may extend the term `method’ to include a procedure that is completed in a single judgment.

§3. But though probably all moral agents have experience of such particular intuitions, and though they constitute a great part of the moral phenomena of most minds, comparatively few are so thoroughly satisfied with them, as not to feel a need of some further moral knowledge even from a strictly practical point of view. For these particular intuitions do not, to reflective persons, present themselves as quite indubitable and irrefragable: nor do they always find when they have put an ethical question to themselves with all sincerity, that they are conscious of clear immediate insight in respect of it. Again, when a man compares the utterances of his conscience at different times, he often finds it difficult to make them altogether consistent: the same conduct will wear a different moral aspect at one time from that which it wore at another, although our knowledge of its circumstances and conditions is not materially changed. Further, we become aware that the moral perceptions of different minds, to all appearance equally competent to judge, frequently conflict: one condemns what another approves. In this way serious doubts are aroused as to the validity of each man’s particular moral judgments: and we are led to endeavour to set these doubts at rest by appealing to general rules, more firmly established on a basis of common consent.

And in fact, though the view of conscience above discussed is one which much popular language seems to suggest, it is not that which Christian and other moralists have usually given. They have rather represented the process of conscience as analogous to one of jural reasoning, such as is conducted in a Court of Law. Here we have always a system of universal rules given, and any particular action has to be brought under one of these rules before it can be pronounced lawful or unlawful. Now the rules of positive law are usually not discoverable by the individual’s reason: this may teach him that law ought to be obeyed, but what law is must, in the main, be communicated to him from some external authority. And this is not unfrequently the case with the conscientious reasoning of ordinary persons when any dispute or difficulty forces them to reason: they have a genuine impulse to conform to the right rules of conduct, but they are not conscious, in difficult or doubtful cases, of seeing for themselves what these are: they have to inquire of their priest, or their sacred books, or perhaps the common opinion of the society to which they belong. In so far as this is the case we cannot strictly call their method Intuitional. They follow rules generally received, not intuitively apprehended. Other persons, however (or perhaps all to some extent), do seem to see for themselves the truth[2] and bindingness of all or most of these current rules. They may still put forward `common consent’ as an argument for the validity of these rules: but only as supporting the individual’s intuition, not as a substitute for it or as superseding it.

Here then we have a second Intuitional Method: of which the fundamental assumption is that we can discern certain general rules with really clear and finally valid intuition. It is held that such general rules are implicit in the moral reasoning of ordinary men, who apprehend them adequately for most practical purposes, and are able to enunciate them roughly; but that to state them with proper precision requires a special habit of contemplating clearly and steadily abstract moral notions. It is held that the moralist’s function then is to perform this process of abstract contemplation, to arrange the results as systematically as possible, and by proper definitions and explanations to remove vagueness and prevent conflict. It is such a system as this which seems to be generally intended when Intuitive or a priori morality is mentioned, and which will chiefly occupy us in Book iii

§ 4. By philosophic minds, however, the `Morality of Common Sense’ (as I have ventured to call it), even when made as precise and orderly as possible, is often found unsatisfactory as a system, although they have no disposition to question its general authority. It is found difficult to accept as scientific first principles the moral generalities that we obtain by reflection on the ordinary thought of mankind, even though we share this thought. Even granting that these rules can be so defined as perfectly to fit together and cover the whole field of human conduct, without coming into conflict and without leaving any practical questions unanswered,—still the resulting code seems an accidental aggregate of precepts, which stands in need of some rational synthesis. In short, without being disposed to deny that conduct commonly judged to be right is so, we may yet require some deeper explanation why it is so. From this demand springs a third species or phase of Intuitionism, which, while accepting the morality of common sense as in the main sound, still attempts to find for it a philosophic basis which it does not itself offer: to get one or more principles more absolutely and undeniably true and evident, from which the current rules might be deduced, either just as they are commonly received or with slight modifications and rectifications.[3]

The three phases of Intuitionism just described may be treated as three stages in the formal development of Intuitive Morality: we may term them respectively Perceptional, Dogmatic, and Philosophical. The last-mentioned I have only defined in the vaguest way: in fact, as yet I have presented it only as a problem, of which it is impossible to foresee how many solutions may be attempted: but it does not seem desirable to investigate it further at present, as it will be more satisfactorily studied after examining in detail the Morality of Common Sense.

It must not be thought that these three phases are sharply distinguished in the moral reasoning of ordinary men: but then no more is Intuitionism of any sort sharply distinguished from either species of Hedonism. A loose combination or confusion of methods is the most common type of actual moral reasoning. Probably most moral men believe that their moral sense or instinct in any case will guide them fairly right, but also that there are general rules for determining right action in different departments of conduct: and that for these again it is possible to find a philosophical explanation, by which they may be deduced from a smaller number of fundamental principles. Still for systematic direction of conduct, we require to know on what judgments we are to rely as ultimately valid.

So far I have been mainly concerned with differences in intuitional method due to difference of generality in the intuitive beliefs recognised as ultimately valid. There is, however, another class of differences arising from a variation of view as to the precise quality immediately apprehended in the moral intuition. These are peculiarly subtle and difficult to fix in clear and precise language, and I therefore reserve them for a separate chapter.[4]

Book III

Chapter I

§1. The effort to examine, closely but quite neutrally, the system of Egoistic Hedonism, with which we have been engaged in the last Book, may not improbably have produced on the reader’s mind a certain aversion to the principle and method examined, even though (like myself) he may find it difficult not to admit the `authority’ of self-love, or the `rationality’ of seeking one’s own individual happiness. In considering `enlightened self-interest’ as supplying a prima facie tenable principle for the systematisation of conduct, I have given no expression to this sentiment of aversion, being anxious to ascertain with scientific impartiality the results to which this principle logically leads. When, however, we seem to find on careful examination of Egoism (as worked out on a strictly empirical basis) that the common precepts of duty, which we are trained to regard as sacred, must be to the egoist rules to which it is only generally speaking and for the most part reasonable to conform, but which under special circumstances must be decisively ignored and broken,—the offence which Egoism in the abstract gives to our sympathetic and social nature adds force to the recoil from it caused by the perception of its occasional practical conflict with common notions of duty. But further, we are accustomed to expect from Morality clear and decisive precepts or counsels: and such rules as can be laid down for seeking the individual’s greatest happiness cannot but appear wanting in these qualities. A dubious guidance to an ignoble end appears to be all that the calculus of Egoistic Hedonism has to offer. And it is by appealing to the superior certainty with which the dictates of Conscience or the Moral Faculty are issued, that Butler maintains the practical supremacy of Conscience over Self-love, in spite of his admission (in the passage before quoted) of theoretical priority in the claims of the latter[5]. A man knows certainly, he says, what he ought to do: but he does not certainly know what will lead to his happiness.

In saying this, Butler appears to me fairly to represent the common moral sense of ordinary mankind, in our own age no less than in his. The moral judgments that men habitually pass on one another in ordinary discourse imply for the most part that duty is usually not a difficult thing for an ordinary man to know, though various seductive impulses may make it difficult for him to do it. And in such maxims as that duty should be performed ‘advienne que pourra’, that truth should be spoken without regard to consequences, that justice should be done `though the sky should fall’, it is implied that we have the power of seeing clearly that certain kinds of actions are right and reasonable in themselves, apart from their consequences;—or rather with a merely partial consideration of consequences[6], from which other consequences admitted to be possibly good or bad are definitely excluded. And such a power is claimed for the human mind by most of the writers who have maintained the existence of moral intuitions; I have therefore thought myself justified in treating this claim as characteristic of the method which I distinguish as Intuitional. At the same time, as I have before observed, there is a wider sense in which the term ‘intuitional’ might be legitimately applied to either Egoistic or Universalistic Hedonism; so far as either system lays down as a first principle—which if known at all must be intuitively known—that happiness is the only rational ultimate end of action. To this meaning I shall recur in the concluding chapters (xiii. and xiv.) of this Book in which I shall discuss more fully the intuitive character of these hedonistic principles. But since the adoption of this wider meaning would not lead us to a distinct ethical method, I have thought it best, in the detailed discussion of Intuitionism which occupies the first eleven chapters of this Book, to confine myself as far as possible to Moral Intuition understood in the narrower sense above defined.

§4. But the question may be raised, whether it is legitimate to take for granted (as I have hitherto been doing) the existence of such intuitions? And, no doubt, there are persons who deliberately deny that reflection enables them to discover any such phenomenon in their conscious experience as the judgment or apparent perception that an act is in itself right or good, in any other sense than that of being the right or fit means to the attainment of some ulterior end. I think, however, that such denials are commonly recognised as paradoxical, and opposed to the common experience of civilised men:—at any rate if the psychological question, as to the existence of such moral judgments or apparent perceptions of moral qualities, is carefully distinguished from the ethical question as to their validity, and from what we may call the `psychogonical’ question as to their origin. The first and second of these questions are sometimes confounded, owing to an ambiguity in the use of the term «intuition»; which has sometimes been understood to imply that the judgment or apparent perception so designated is true. I wish therefore to say expressly, that by calling any affirmation as to the rightness or wrongness of actions «intuitive», I do not mean to prejudge the question as to its ultimate validity, when philosophically considered: I only mean that its truth is apparently known immediately, and not as the result of reasoning. I admit the possibility that any such «intuition» may turn out to have an element of error, which subsequent reflection and comparison may enable us to correct; just as many apparent perceptions through the organ of vision are found to be partially illusory and misleading: indeed the sequel will show that I hold this to be to an important extent the case with moral intuitions commonly so called.

The question as to the validity of moral intuitions being thus separated from the simple question `whether they actually exist’, it becomes obvious that the latter can only be decided for each person by direct introspection or reflection. It must not therefore be supposed that its decision is a simple matter, introspection being always infallible: on the contrary, experience leads me to regard men as often liable to confound with moral intuitions other states or acts of mind essentially different from them,—blind impulses to certain kinds of action or vague sentiments of preference for them, or conclusions from rapid and half-unconscious processes of reasoning, or current opinions to which familiarity has given an illusory air of self-evidence. But any errors of this kind, due to careless or superficial reflection, can only be cured by more careful reflection. This may indeed be much aided by communication with other minds; it may also be aided, in a subordinate way, by an inquiry into the antecedents of the apparent intuition, which may suggest to the reflective mind sources of error to which a superficial view of it is liable. Still the question whether a certain judgment presents itself to the reflective mind as intuitively known cannot be decided by any inquiry into its antecedents or causes[7].

It is, however, still possible to hold that an inquiry into the Origin of moral intuitions must be decisive in determining their Validity. And in fact it has been often assumed, both by Intuitionists and their opponents, that if our moral faculty can be shown to be `derived’ or `developed’ out of other pre-existent elements of mind or consciousness, a reason is thereby given for distrusting it; while if, on the other hand, it can be shown to have existed in the human mind from its origin, its trustworthiness is thereby established. Either assumption appears to me devoid of foundation. On the one hand, I can see no ground for supposing that a faculty thus derived, is, as such, more liable to error than if its existence in the individual possessing it had been differently caused: to put it otherwise, I cannot see how the mere ascertainment that certain apparently self-evident judgments have been caused in known and determinate ways, can be in itself a valid ground for distrusting this class of apparent cognitions. I cannot even admit that those who affirm the truth of such judgments are bound to show in their causes a tendency to make them true: indeed the acceptance of any such onus probandi would seem to me to render the attainment of philosophical certitude impossible. For the premises of the required demonstration must consist of caused beliefs, which as having been caused will equally stand in need of being proved true, and so on ad infinitum: unless it be held that we can find among the premises of our reasonings certain apparently self-evident judgments which have bad no antecedent causes, and that these are therefore to be accepted as valid without proof. But such an assertion would be an extravagant paradox: and, if it be admitted that all beliefs are equally in the position of being effects of antecedent causes, it seems evident that this characteristic alone cannot serve to invalidate any of them.

I hold, therefore, that the onus probandi must be thrown the other way: those who dispute the validity of moral or other intuitions on the ground of their derivation must be required to show, not merely that they are the effects of certain causes, but that these causes are of a kind that tend to produce invalid beliefs. Now it is not, I conceive, possible to prove by any theory of the derivation of the moral faculty that the fundamental ethical conceptions `right’ or `what ought to be done’, `Good’ or `what it is reasonable to desire and seek’, are invalid, and that consequently all propositions of the form `X is right’ or `good’ are untrustworthy: for such ethical propositions, relating as they do to matter fundamentally different from that with which physical science or psychology deals, cannot be inconsistent with any physical or psychological conclusions. They can only be shown to involve error by being shown to contradict each other; and such a demonstration cannot lead us cogently to the sweeping conclusion that all are false. It may, however, be possible to prove that some ethical beliefs have been caused in such a way as to make it probable that they are wholly or partially erroneous: and it will hereafter be important to consider how far any Ethical intuitions, which we find ourselves disposed to accept as valid, are open to attack on such psychogonical grounds. At present I am only concerned to maintain that no general demonstration of the derivedness or developedness of our moral faculty can supply an adequate reason for distrusting it.

On the other hand, if we have been once led to distrust our moral faculty on other grounds—as (e.g.) from the want of clearness and consistency in the moral judgments of the same individual, and the discrepancies between the judgments of different individuals—it seems to me equally clear that our confidence in such judgments cannot properly be re-established by a demonstration of their `originality’. I see no reason to believe that the `original’ element of our moral cognition can be ascertained; but if it could, I see no reason to hold that it would be especially free from error.

§5. How then can we hope to eliminate error from our moral intuitions? One answer to this. question was briefly suggested in a previous chapter where the different phases of the Intuitional Method were discussed. It was there said that in order to settle the doubts arising from the uncertainties and discrepancies that are found when we compare our judgments on particular cases, reflective persons naturally appeal to general rules or formulae: and it is to such general formulae that Intuitional Moralists commonly attribute ultimate certainty and validity. And certainly there are obvious sources of error in our judgments respecting concrete duty which seem to be absent when we consider the abstract notions of different kinds of conduct; since in any concrete case the complexity of circumstances necessarily increases the difficulty of judging, and our personal interests or habitual sympathies are liable to disturb the clearness of our moral discernment. Further, we must observe that most of us feel the need of such formulae not only to correct, but also to supplement, our intuitions respecting particular concrete duties. Only exceptionally confident persons find that they always seem to see clearly what ought to be done in any case that comes before them. Most of us, however unhesitatingly we may affirm rightness and wrongness in ordinary matters of conduct, yet not unfrequently meet with cases where our unreasoned judgment fails us; and where we could no more decide the moral issue raised without appealing to some general formula, than we could decide a disputed legal claim without reference to the positive law that deals with the matter.

And such formulae are not difficult to find: it only requires a little reflection and observation of men’s moral discourse to make a collection of such general rules, as to the validity of which there would be apparent agreement at least among moral persons of our own age and civilisation, and which would cover with approximate completeness the whole of human conduct. Such a collection, regarded as a code imposed on an individual by the public opinion of the community to which he belongs, we have called the Positive Morality of the community: but when regarded as a body of moral truth, warranted to be such by the consensus of mankind,—or at least of that portion of mankind which combines adequate intellectual enlightenment with a serious concern for morality—it is more significantly termed the morality of Common Sense.

When, however, we try to apply these currently accepted principles, we find that the notions composing them are often deficient in clearness and precision. For instance, we should all agree in recognising Justice and Veracity as important virtues; and we shall probably all accept the general maxims, that `we ought to give every man his own’ and that `we ought to speak the truth’: but when we ask (1) whether primogeniture is just, or the disendowment of corporations, or the determination of the value of services by competition, or (2) whether and how far false statements may be allowed in speeches of advocates, or in religious ceremonials, or when made to enemies or robbers, or in defence of lawful secrets, we do not find that these or any other current maxims enable us to give clear and unhesitating decisions. And yet such particular questions are, after all, those to which we naturally expect answers from the moralist. For we study Ethics, as Aristotle says, for the sake of Practice: and in practice we are concerned with particulars.

Hence it seems that if the formulae of Intuitive Morality are really to serve as scientific axioms, and to be available in clear and cogent demonstrations, they must first be raised—by an effort of reflection which ordinary persons will not make—to a higher degree of precision than attaches to them in the common thought and discourse of mankind in general. We have, in fact, to take up the attempt that Socrates initiated, and endeavour to define satisfactorily the general notions of duty and virtue which we all in common use for awarding approbation or disapprobation to conduct. This is the task upon which we shall be engaged in the nine chapters that follow. I must beg the reader to bear in mind that throughout these chapters I am not trying to prove or disprove Intuitionism, but merely by reflection on the common morality which I and my reader share, and to which appeal is so often made in moral disputes, to obtain as explicit, exact, and coherent a statement as possible of its fundamental rules.

[1] It must, however, be remembered that Aristotle regarded the general proposition obtained by induction as really more certain (and in a higher sense knowledge) than the particulars through which the mind is led up to it.

[2] Strictly speaking, the attributes of truth and falsehood only belong formally to Rules when they are changed from the imperative mood («Do X») into the indicative («X ought to be done»).

[3] It should be observed that such principles will not necessarily be «intuitional» in the narrower sense that excludes consequences; but only in the wider sense as being self-evident principles relating to `what ought to be’.

[4] NOTE.—Intuitional moralists have not always taken sufficient care in expounding their system to make clear whether they regard as ultimately valid, moral judgments on single acts, or general rules prescribing particular kinds of acts, or more universal and fundamental principles. For example, Dugald Stewart uses the term «perception» to denote the immediate operation of the moral faculty; at the same time, in describing what is thus perceived, he always seems to have in view general rules.

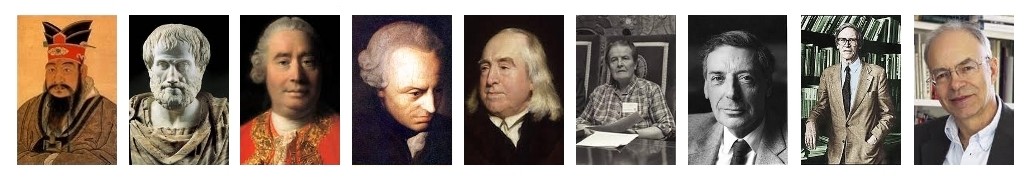

Still we can tolerably well distinguish among English ethical writers those who have confined themselves mainly to the definition and arrangement of the Morality of Common Sense, from those who have aimed at a more philosophical treatment of the content of moral intuition. And we find that the distinction corresponds in the main to a difference of periods: and that—what perhaps we should hardly have expected—the more philosophical school is the earlier. The explanation of this may be partly found by referring to the doctrines in antagonism to which, in the respective periods, the Intuitional method asserted and developed itself. In the first period all orthodox moralists were occupied in refuting Hobbism. But this system, though based on Materialism and Egoism, was yet intended as ethically constructive. Accepting in the main the commonly received rules of social morality, it explained them as the conditions of peaceful existence which enlightened self interest directed each individual to obey; provided only the social order to which they belonged was not merely ideal, but made actual by a strong government. Now no doubt this view renders the theoretical basis of duty seriously unstable; still, assuming a decently good government, Hobbism may claim to at once explain and establish, instead of undermining, the morality of Common Sense. And therefore, though some of Hobbes’ antagonists (as Cudworth) contented themselves with simply reaffirming the absoluteness of morality, the more thoughtful felt that system must be met by system and explanation by explanation, and that they must penetrate beyond the dogmas of common sense to some more irrefragable certainty. Arid so, while Cumberland found this deeper basis in the notion of «the common good of all Rationals» as an ultimate end, Clarke sought to exhibit the more fundamental of the received rules as axioms of perfect self-evidence, necessarily forced upon the mind in contemplating human beings and their relations. Clarke’s results, however, were not found satisfactory: and by degrees the attempt to exhibit morality as a body of scientific truth fell into discredit, and the disposition to dwell on the emotional side of the moral consciousness became prevalent. But when ethical discussion thus passed over into psychological analysis and classification, the conception of the objectivity of duty, on which the authority of moral sentiment depends, fell gradually out of view: for example, we find Hutcheson asking why the moral sense should not vary in different human beings, as the palate does, without dreaming that there is any peril to morality in admitting such variations as legitimate. When, however, the new doctrine was endorsed by the dreaded name of Hume, its dangerous nature, and the need of bringing again into prominence the cognitive element of moral consciousness, were clearly seen: and this work was undertaken as a part of the general philosophic protest of the Scottish School against the Empiricism that had culminated in Hume. But this school claimed as its characteristic merit that it met Empiricism on its own ground, and showed among the facts of psycho logical experience which the Empiricist professed to observe, the assumptions which he repudiated. And thus in Ethics it was led rather to expound and reaffirm the morality of Common Sense, than to offer any profounder principles which could not be so easily supported by an appeal to common experience.

[5] It may seem, he admits, that «since interest, one’s own happiness, is a manifest obligation», in any case in which virtuous action appears to be not conducive to the agent’s interest, he would be «under two contrary obligations,i.e. under none at all. But», he urges, «the obligation on the side of interest really does not remain. For the natural authority of the principle of reflection or conscience is an obligation … the most certain and known: whereas the contrary obligation can at the utmost appear no more than probable: since no man can be certain in any circumstances that vice is his interest in the present world, much less can he be certain against another: and thus the certain obligation would entirely supersede and destroy the uncertain one.»—(Preface to Butler’s Sermons.)

[6] I have before observed (Book i. chap. viii. §1) that in the common notion of an act we include a certain portion of the whole series of changes partly caused by the volition which initiated the so-called act.

[7] I cannot doubt that every one of our cognitive faculties,—in short the human mind as a whole,—has been derived and developed, through a gradual process of physical change, out of some lower life in which cognition, properly speaking, had no place. On this view, the distinction between `original’ and `derived’ reduces itself to that between `Prior’ and `Posterior’ in development: and the fact that the moral faculty appears somewhat later in the process of evolution than other faculties can hardly be regarded as an argument against the validity of moral intuition; especially since this process is commonly conceived to be homogeneous throughout. Indeed such a line of reasoning would be suicidal; as the cognition that the moral faculty is developed is certainly later in development than moral cognition, and would therefore, by this reasoning, be less trustworthy.